THE GENIUS OF OLIN STEPHENS

After the behind-the-scenes manoeuvrings of the 1964 British challenge, the pathway appeared clear for an Australian assault on the America’s Cup in 1967 but if the colourful Sir Frank Packer thought that he would have it all his own way, he was sorely mistaken. Just two days after Constellation’s win, Packer issued his challenge through the Royal Sydney Yacht Squadron only to find that Otto Meik, Commodore of the Royal Melbourne Yacht Squadron had done the same. Meanwhile the New York Yacht Club had also accepted a first French challenge from the Yacht Club d’Hyères on behalf of Baron Marcel Bich, the French manufacturer and founder of the Bic pen empire, and the sparks flew.

Packer, having stood aside in 1964, assumed that he would be the designated challenger with a re-built Gretel, and was vocal of his disapproval to race in a series of challenger selection trials. These were the days that preceded the Challenger of Record status and challenger selection regattas. The waters were muddied further when another group from Melbourne, led by ice-cream tycoon Emil Christensen, came forward with a funded and well-staffed syndicate that included Jock Sturrock who had jumped ship from the Packer camp. Christensen had also appointed the young Sydney designer Warwick Hood who had worked with Alan Payne as an understudy on the design of Gretel.

After much acrimony, Packer accepted the conditions to decide the challenger that would represent the Royal Sydney Yacht Squadron of which he was commodore and with the Meik and Bich challenges falling away, it was a two-way fight for selection between the old but re-built Gretel of 1962 and the new 12 Metre that was named ‘Dame Pattie’ after Sir Robert Menzies’ wife. In effect Packer brought a knife to a gunfight with Gretel significantly off the pace compared with the well thought-out and seemingly money-no-object campaign of Dame Pattie that was tank-tested at the Sydney University facilities alongside innovative sail cloth development to match the Hood sailcloth that was used on the American 12 Meters. In race after race, Gretel came up short and although flattering to the designers of Dame Pattie, it was to prove more by better sailing and cohesive crew-work than any speed advantage.

Over in America, the Australian threat was met with genius in the form of Olin Stephens for what he created in the design of Intrepid was nothing short of revolutionary and set the course for decades of yacht design. By adding a trim tab to the trailing edge of the keel and separating the rudder from the keel completely via a skeg, 12 Meters were never the same again. Testing the model of Intrepid at one thirteenth scale in the tank proved productive for Stephens whose fixation with achieving the best possible ratio of sail area to wetted surface area without losing stability was to become his design mantra. His evolutionary but revolutionary take on design all came together in Intrepid and as it would show in trials and the subsequent Match was at least a generation ahead of the accepted design wisdom of the day.

Dame Pattie on the other hand was old school. A heavy displacement 12 Meter with a long waterline length, small keel area, minimum beam and low wetted surface area ended up costing her on sail area to accommodate for the greater length on the waterline. Whilst she was a convincing winner of the trails through the January of 1967 in Sydney, those trials were dominated by the almost mutiny aboard Gretel under the dictatorial manner of Sir Frank Packer.

When Dame Pattie suffered a dis-masting in late 1966, Packer decided to effectively chop up Gretel, making significant modifications to her underside creating a sharper entry forward and a deep-V afterbody. Only the deck survived, but the theory in Packer’s mind was that the grandfathering rule that allowed Gretel to use her American-made sails and deck gear from the 1962 challenge would outweigh design advances being made in the newer boats. He was sorely wrong. In the final trials, Dame Pattie was a class apart and duly selected as the challenging yacht for the Royal Sydney Yacht Squadron. Packer saw red, and instead of shipping Gretel to Newport to either continue the trials or act as a tune-up partner for Dame Pattie, he withdrew the boat from any further sailing.

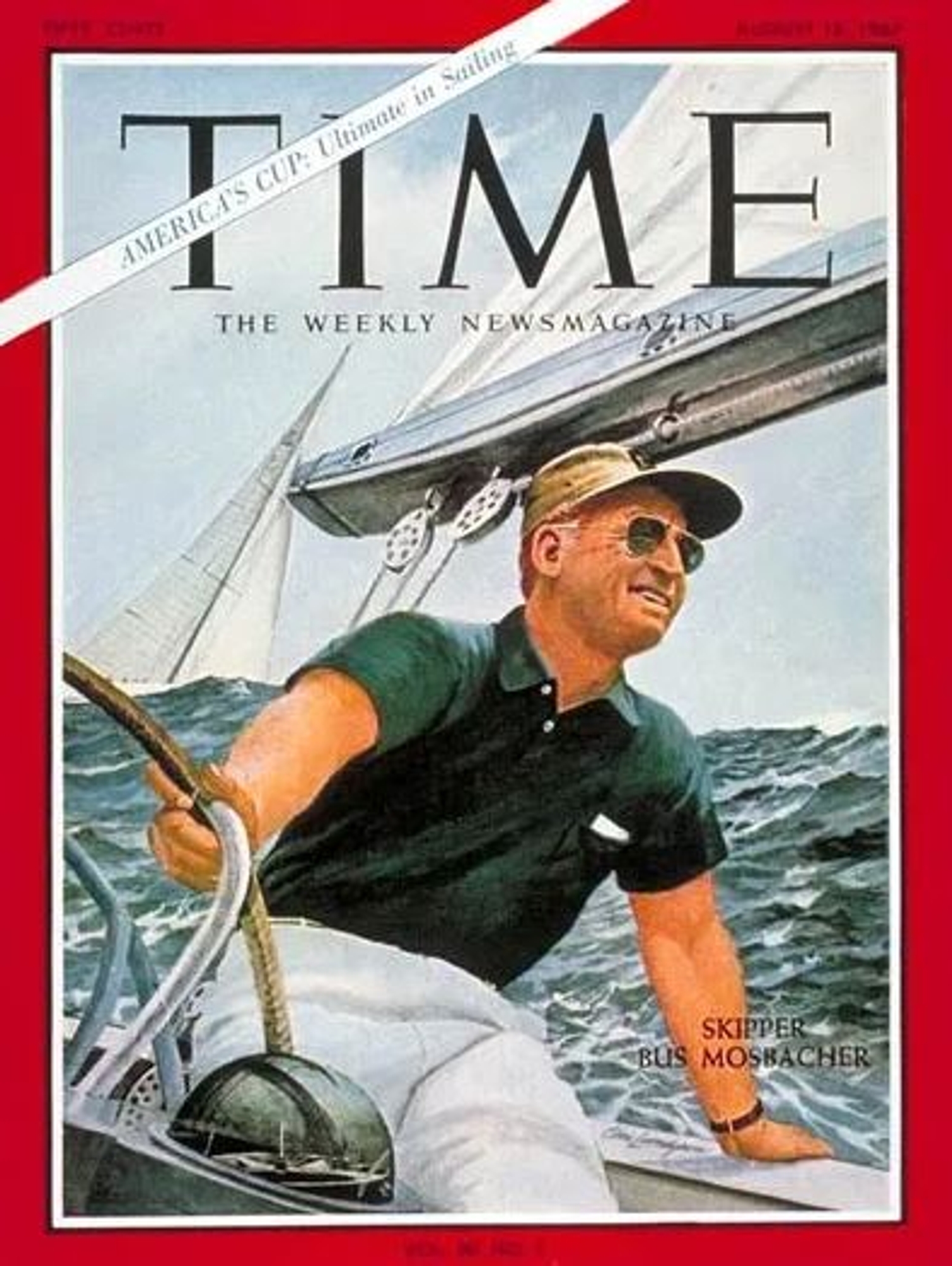

When they arrived in Newport in the summer of 1967, the Australians met a well-organised defence campaign that was well into its trails. Bus Mosbacher had assembled an all-star, experienced crew for Intrepid whilst Briggs Cunningham commissioned Columbia to be heavily modified by the Sparkman & Stephens design office and added Bill Ficker as helmsman. Constellation had been purchased from Baron Marcel Bich and installed Bob Mcullough on the helm whilst the aged American Eagle was entered by George Hinman to form a four-way competition to elicit the best race tuning and decide the defender for the New York Yacht Club. As racing continued on an almost daily basis through August 1967 in the defence trials, the stand-out performers were Intrepid and Columbia. What was notable was the come-from-behind nature of Intrepid’s afterguard, something that Bus Mosbacher was acutely aware of with a faster boat. What Mosbacher realised and later said was that: “The quickest way to lose with Intrepid was to ‘foul out’…I tried to start Intrepid to windward of the competition and stay out of trouble. Consequently, most of our starts were pretty dull for the spectators.”

Dull yet effective. In the final trials against Columbia, with American Eagle and Constellation both excluded, Intrepid went on a remarkable six race unbeaten streak, winning by considerable margins, and there was no doubt in the New York Yacht Club Committee’s minds as to who their pick was for the defence. After a resounding 3 minute and 15 second win on August 24th, 1967, Henry S. Morgan, Chairman of the Cup Committee, greeted the sailors at their berth with the words: “Gentlemen, I am happy to inform you that you have been selected to defend the America’s Cup.”

All was set for the much-anticipated Intrepid versus Dame Pattie match-up, but the regatta soured considerably before the two met and, once again in the America’s Cup, rule interpretation was at the very heart of the conflict. The accepted practice for what was known as ‘light measurement’ saw the Americans remove winches and other equipment whilst leaving a mainsail and jib staysail onboard as the only sails. At the flotation test, undertaken by the NYYC’s official measurer Bob Blumenstock, Warwick Hood, the designer of Dame Pattie was aboard the measurement boat with Olin Stephens as Blumenstock did his work. Hood was heard to voice displeasure at what he felt was the Americans being smart with their approach and after that day’s practice sail, the crew of Intrepid came ashore to find that an official protest had been lodged despite Stephens and Hood discussing the matter beforehand.

Claims of ‘cheating’ were bandied around the press and Mosbacher was incensed not only at having to waste a day having the boat re-measured but at the perceived slight by Dame Pattie’s skipper Jock Sturrock whom he had known and competed against for some years and who he called a friend.

Mosbacher was well-versed in rules disputes and cited the 1962 issues around measurement with Gretel and the way that the matter was resolved in a gentlemanly fashion with the Australian designer Alan Payne. Sturrock’s defence of the actions with Dame Pattie alluded to external forces, with Mosbacher relaying: “Jock indicated that he regretted the situation very much, but he also led me to believe that he was not a free agent in this area.” Gamesmanship in the America’s Cup is old as the hills.

Time magazine had given over the front cover of its magazine to Mosbacher on the 18th of August 1967 with the returning skipper famously describing the Cup as “the closest thing to a Holy Grail in sport,” before adding: “The contest, not the old Victorian silver ewer, is the thing. In the demands it makes on boat and man, it is the ultimate, the very pinnacle in yachting. What started 116 years ago as a gentlemen’s lark, has become a proving ground for technocrats, a vast public spectacle, an affair of national pride, purpose and prestige that so far has cost the competitors, winners and losers combined, an estimated $50 million—with no guarantees on the investment except that somebody would win and somebody else would lose.”

In 1967, Intrepid was the only winner and with the most beautiful 7.5-ounce Hood mainsail that stood up perfectly as opposed to Dame Pattie’s 12.5 ounce, she was a class apart. The opening race victory in a steady 18-20 knot easterly and short, sharp seas, by a margin of 5 minutes and 58 seconds over six legs was indicative of the whitewash that the Australians were about to face. Intrepid had speed on every angle as Olin Stephens later commented: “Another thing that was nice about the boat was that she would go no matter how you trimmed her. If you wanted to pinch her, you could pinch her, and if you wanted to rap her off, she was very fast on a close reach. This was very nice to have up your sleeve.”

Race two was held in the remnants of the easterly breeze from the day before and produced much lighter, flukier conditions out on the Newport racecourse. After a very close gauge start, Dame Pattie forced Intrepid to tack away after coming up sharp from leeward in a pinching match. Once clear on port tack, Mosbacher drove for speed and by the time they returned was clear ahead of the Australian’s bow. From there on Intrepid gained steadily on every leg, noticeably pulling away downwind and by the fifth mark had a lead of over five minutes. By the finish, sailing under the wrong genoa, Intrepid crossed with a delta of 3 minutes and 36 seconds to take a 2-0 lead in the series.

Race three saw the return of the breeze into a range that suited Intrepid with a 15-20 knot north-easterly. Once again Mosbacher positioned the defender to windward on the starting line, quickly easing into the command position and after two short tacks found themselves on the lay line after a 15-degree favourable shift. The only drama of the day for the Americans was caused by external factors as a US Coastguard helicopter was called in to rescue the sailors onboard a vessel that had ventured onto the racecourse and the subsequent downdraft from the helicopter had capsized the boat. Whilst the Coastguard was rescuing the occupants in distress, Mosbacher and his crew were on a direct line to the incident and as they approached the scene, the helicopter started to move backwards, narrowing the angle that the Americans had chosen to go around its tail propeller. It was a close-run thing with Mosbacher later saying that: “…as she backed down on us, we were all scared to death, but we were delighted when it was all over almost before it started.” At the top mark the incident had cost Mosbacher little and Intrepid rounded 1 minute and 21 seconds ahead before extending out and closing the race with a 4 minute and 41 second drubbing. The writing was writ large on the wall for the Australians.

For what was to be the final race of the America’s Cup Match in 1967, dense fog greeted the two yachts on Monday 18th September and for all the world it looked like a postponement would be called. However, at 2.10pm and only a few minutes before the time limit expended, the NYYC Race Committee saw a clearing and got racing underway. It was a shrewd move for as the yachts started on opposite tacks, within half a leg, the fog had lifted to afford a visibility of over 3 miles. Intrepid controlled the race from the first cross and with the Australians convinced that their winch system was a faster solution, a short tacking duel ensued. The reality was that Intrepid gained on every tack and by the top mark held a customary lead of some 1 minute and 25 seconds. With the America’s Cup in sight, Mosbacher plied his advantage relentlessly over the next three legs opening up a 3 minute and 54 second lead by the final mark and it was only on the final leg, with the competition won, that Dame Pattie made any impression. The winning margin was 3 minutes and 35 seconds at the finish.

As the boats came back to Newport almost in the dark, the communique was sent to Donald Kipp, Secretary of the New York Yacht Club, from Harry Anderson Jr Chairman of the NYYC Race Committee declaring that: “Intrepid won the best four out of seven races from Dame Pattie and thereby the Match for the America’s Cup.”

On reflection afterwards, Mosbacher’s sense of relief at a job well done was palpable: “It is very hard to describe just how I felt when it was all over. There was a sense of satisfaction in having accomplished what we set out to do in the best way we knew how. This was strictly a team effort…the fact that we had a fine boat didn't lighten the load. No one on Intrepid let down for an instance until that last race was over.”

Sparkman & Stephens later recorded the revolutionary Intrepid in their ship register saying: “Designed by Sparkman & Stephens and built and launched by the Minneford Yacht Yard, City Island, NY in 1967. Design number 1834 was Sparkman & Stephen’s sixth 12 Metre, incorporating a revolutionising innovative hull shape, first fin and skeg configuration with a trim tab. Adding to greater stability, the crew and winches were moved below deck to facilitate a lower innovative bending boom, with the top portion of the mast made out of titanium. She easily won the 1967 America’s Cup Races 4-0 against Dame Pattie.”

Olin Stephen’s himself was more circumspect saying: “Intrepid was not a super-boat. She had a hull that was slightly faster upwind. Her sails were a bit better. The crew a shade sharper. And that all added up to a successful defender.”

The America’s Cup was safe in the New York Yacht Club that summer in 1967 by the genius of the Cup’s greatest designer, but the competition was getting even more determined.